By Ajay jagga

Public Interest Litigation is commonly known as PIL in India. The initial inspiration for Indian PIL came from the American concept of Public Interest Litigation and the class actions of the 1960s. PIL means litigation for the protection of public interest or in the interest of public. It is the litigation introduced in the court of Law, not by the aggrieved party but by any person/association of persons or by the court itself. It is not necessary, for the exercise of the court’s jurisdiction, that the person/s who is/are the victim of the violations of his or her right should personally or through the counsel approach the court. It is said to be the strategy developed by the Supreme Court of India to secure the observance of the law by the Government and its agencies, and to extend social justice to the large masses of underprivileged persons in the country.

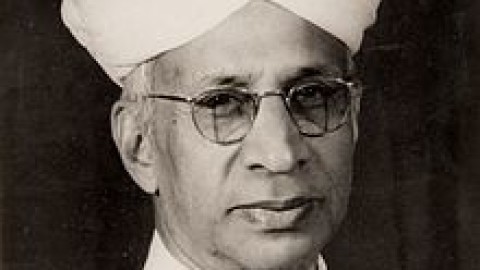

Prior to the 1980s, only the aggrieved party could approach the courts for justice. However, post 1980s and after the emergency era, the apex court decided to reach out to the people and hence it devised an innovative way wherein a person or a civil society group could approach the supreme court seeking legal remedies in cases where public interest is at stake. Justice P. N. Bhagwati and Justice V. R. Krishna Iyer were among the first judges to admit PIL’s in the court.

According to a controversial study by Hans Dembowski, PIL has been successful in the sense of making official authorities accountable to the public or civil society organisations.

The Apex Court has been much concerned with the social justice, since 1977. The year 1977 was actually the beginning of the “activist phase†of the Supreme Court of India. The Apex Court has remained firm in its avowed mission and maintained that it was the Constitutional duty of the Court to provide “justice” to the masses. The stand is absolutely in tune with Constitution of India and in order to give effects to the words expressed in its preamble “to secure to all its citizens Justice, social, economic and political; Liberty, of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship; Equality of status and of opportunity; and to promote among them all Fraternity assuring the dignity of the individual…”

The Constitution of India has guaranteed to the people of India certain basic democratic rights called the “Fundamental Rights” (Articles 13 to 32), akin to the American Bill of Rights. The Fundamental Rights include the right to equality before law; prohibition of discrimination on the ground of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth, freedom of speech, of assembly, of movement, of forming association, of residence, of profession, trade or business; protection of life and liberty; protection against arrest and detention, and various other rights. These rights are enforceable against the State and its agencies. Any person aggrieved by a breach of any of his rights may move the local High Court or the SCI seeking enforcement of the right. Any law enacted by the legislature or any executive action may be declared to void by the Court in the event of breach. The Court may also remedy any governmental inaction or neglect by issuing a writ or a mandate to the executive authority. The right to judicial remedy is itself a guaranteed right.

To make its strategy feasible, the SCI (Supreme Court of India) worked out its plan by taking two historical steps. The first step taken in this direction was amending the implementation of the word “locus standi,†which allows only the aggrieved person or victim to approach the Court for seeking relief. This was infact the main obstacle in providing access to justice to the disadvantaged or economically weaker section of the society. Accordingly the rule of standing was withdrawn in the case of PIL. The SCI made it clear that any bona fide person or public spirited individual or association or NGO to move to the Court on behalf of those who were unable to approach the Court directly.

Subsequently SCI felt that permitting any member of public to approach the court in public interest would not be enough to encourage a person acting ‘pro bono publico’ to shoulder the responsibility, burden of litigation with its costs and hassles. So in order to remove this obstacle and to make the PIL convenient and without costs for public spirited persons, the SCI took the second historical step by simplifying in the procedural law: i.e. merely writing a letter to the Court would be enough to permit the Court to take cognizance of the matter and start necessary proceedings. This proved to be a great success as many matters of public interest were brought to the notice of SCI by way of simple letters and the SCI ordered for urgent actions in interest of public at large.

PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION is not defined in any statute or in any act. It has been interpreted by judges to consider the intent of public at large. Although, the main and only focus of such litigation is only “Public Interest” there are various areas where a PIL can be filed. For example

– Violation of basic human rights of the poor

– Air or water Pollution

– Implementation of a Law

– Content or conduct of government policy

– Compel municipal authorities to perform a public duty.

– Violation of religious rights or other basic fundamental rights.

PIL as it has developed in recent years marks a significant departure from traditional judicial proceedings. It now dominates the public perception of the Supreme Court. The Court is now seen as an institution not only reaching out to provide relief to citizens but even venturing into formulating policy which the State must follow. At the time of Independence, court procedure was drawn from the Anglo-Saxon system of jurisprudence. The majority of citizens were/are unaware of their legal rights, and much less in a position to assert them. The guarantees of fundamental rights and the assurances of directive principles, described as the ‘conscience of the Constitution’, would have remained empty promises for the majority of illiterate and indigent citizens under adversarial proceedings. PIL has been a conscious attempt to transform the promise into reality.

Since the inception of PIL, the SCI and the various state High Courts various subject matters dealt with and including, giving relief to unorganized workers in the matter of their wages, improving working conditions, housing issues, civic services, environmental issues, consumer issues, educational matters, prisoners in jail, prevention of torture of under trial prisoners, maintenance of jails. It also dealt with matters like prevention of pollution of the river Ganges, reservation of a jungle as reserve forest, admission to schools and holding of examinations in colleges.

According to the jurisprudence of Article 32 of the Constitution of India, “The right to move the Supreme Court by appropriate proceedings for the enforcement of the rights conferred by this part is guaranteedâ€. Ordinarily, only the aggrieved party has the right to seek redress under Article 32.

In 1981 Justice P. N. Bhagwati in .S. P. Gupta v. Union of India, 1981 (Supp) SCC 87, articulated the concept of PIL as follows, “Where a legal wrong or a legal injury is caused to a person or to a determinate class of persons by reason of violation of any constitutional or legal right or any burden is imposed in contravention of any constitutional or legal provision or without authority of law or any such legal wrong or legal injury or illegal burden is threatened and such person or determinate class of persons by reasons of poverty, helplessness or disability or socially or economically disadvantaged position unable to approach the court for relief, any member of public can maintain an application for an appropriate direction, order or writ in the High Court under Article 226 and in case any breach of fundamental rights of such persons or determinate class of persons, in this court under Article 32 seeking judicial redress for the legal wrong or legal injury caused to such person or determinate class of persons.â€

Supreme Court in Indian Banks’ Association, Bombay and ors v. M/s Devkala Consultancy Service and Ors., J. T. 2004 (4) SC 587, held that “In an appropriate case, where the petitioner might have moved a court in her private interest and for redressal of the personal grievance, the court in furtherance of Public Interest may treat it a necessity to enquire into the state of affairs of the subject of litigation in the interest of justice. Thus a private interest case can also be treated as public interest caseâ€.

In a historical PIL (Citizen for Democracy v. State of Assam, (1995) 3SCC 743), the S. C. declared that the handcuffs and other fetters shall not be forced upon a prisoner while lodged in jail or while in transport or transit from one jail to another or to the court or back.

This blessing is also not untouched by abuses and aberrations as well. The credentials and bona fide used to be used to be a sound screening process at the admission level of a PIL. In its absence frivolous PILs started reaching courts, which were actually private disputes. The lure of soft justice and procedural relaxations has induced many ingenuine persons, with private vested interest, misusing this litigation in the guise of a public spirited person or organization. The position in some PILs became so bad that the Apex Court had to impose a fine of One lac Indian rupees on the petitioner in a matter in 2006.

Recently there have been two observations in the Apex Court on the PIL matter, first when a two-judge bench criticized the judicial over reach and said Judges should not behave like emperors and questioned court orders on PILs. With this the Delhi High Court deferred the hearing of PILs till things were clearer. The second observation came a after a couple of days i.e. on December 13,2007 when a PIL was sent to a three judge bench headed by the Chief Justice of India Justice K G Balakrishnan who made it clear that PILs for the right cause be heard and agreed to examine a PIL on the plights of widows in Brindavan. Chief Justice of India said “we are not bound by the order (the earlier order made by two judge bench), so the genuine PILs will be taken up by the Supreme Court.”

There is no doubt that for some years the PILs were the lone weapon against the unresponsive system. The Chief Justice’s correction on the PIL restores hope for the people.

In nutshell, the fact is that, due to the frivolous PILs the genuine matters should not suffer. The absence of personal interest of the petitioner in a PIL remains the acid test. Moreover it is established rule of law that an accused may go scot free but an innocent should not be hanged.